Modern Engineering for Slope Stabilization

No two slopes are ever the same. Each layer of soil, rainfall intensity, and subsurface water condition creates a unique system that affects the balance of forces beneath the earth’s surface.

One thing, however, remains certain: soil will always seek to move downward, and without engineering intervention, even small displacements can evolve into major landslides.

Soil stabilization is not merely about strengthening a slope, it’s about controlling how soil responds to changes in pressure, water, and load. This approach has now become a fundamental principle in the design of roads, dams, and open-pit mines around the world.

The Physics Behind Slope Stabilization

The stability of a slope depends on the balance between the driving forces (gravity and water pressure) and the resisting forces (shear strength and structural support). The goal of engineering design is to increase resisting forces without significantly altering the slope geometry.

The three key factors are:

- Soil or rock properties (cohesion, friction angle, unit weight),

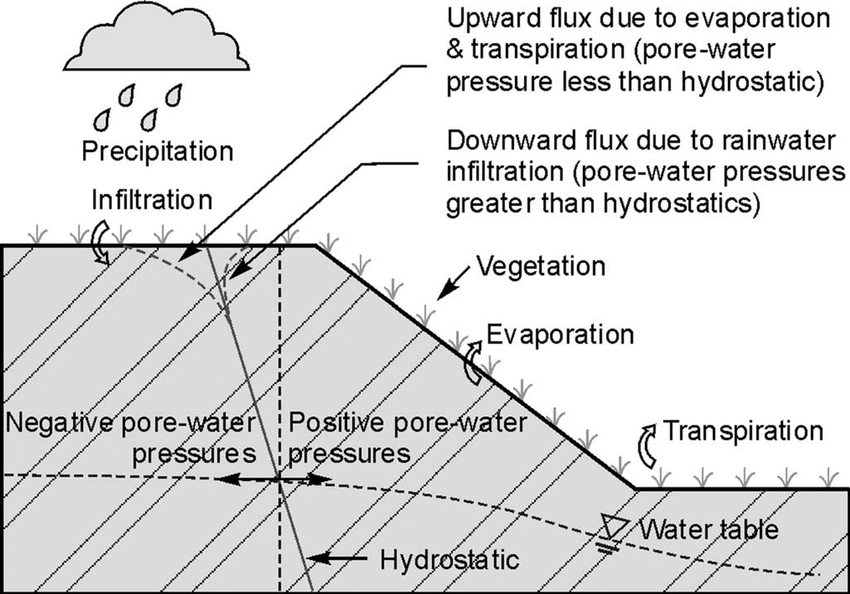

- Pore-water pressure and drainage conditions,

- External loading and slope geometry.

Stability analysis is typically conducted using methods such as Bishop, Janbu, or Finite Element Modeling (FEM) with software like Slide2 or Plaxis, targeting a Factor of Safety (FoS) of at least 1.3–1.5.

Core Technologies for Slope Stabilization

In modern field applications, engineers often use a combination of three technologies:

- Geogrid & Mesh:

Designed to reinforce the surface layer of slopes and retain loose particles. Polymer-based geogrids are used for soil slopes, while steel meshes are applied on rock surfaces.

Advantages: lightweight, easy to install, and compatible with green vegetation systems.

- Rock Bolt / Soil Nail:

Anchoring systems that “lock” the internal mass of soil or rock in place. Installation involves drilling, grouting, and securing with bearing plates.

Benefits: increase internal stiffness and prevent layer separation or block movement.

- Shotcrete:

Sprayed concrete applied as a protective final layer. It reduces erosion, strengthens the mesh and bolt heads, and distributes surface loads evenly.

Best variant: Steel Fiber Reinforced Shotcrete (SFRS) for high strength and durability.

Field Implementation Process

Step 1 – Investigation & Design

Geotechnical testing of soil and rock is performed to identify potential slip surfaces and determine the most appropriate stabilization system.

Step 2 – Installation of Reinforcement

Mesh or geogrid is installed following the slope contour; rock bolts are anchored across the slip zone; then shotcrete (50–100 mm thick) is applied to seal and strengthen the surface.

Step 3 – Drainage & Monitoring

Weep holes are added to relieve pore-water pressure, while deformation sensors and piezometers are installed for long-term slope monitoring.

Innovation & Future Directions

Recent engineering approaches combine structural design with smart and sustainable technologies, such as:

- Bio-shotcrete, which uses calcite-producing microorganisms to fill pores and prevent cracking;

- IoT-based slope sensors, providing real-time data on movement, humidity, and stress levels.

These innovations make slope stabilization not only strong and efficient but also adaptive and sustainable in the long term.

Conclusion

“Soil stabilization for slopes” is more than just reinforcing an earthen wall, it’s about reshaping how soil behaves and interacts with natural forces.

Through the integration of geogrid, rock bolt, and shotcrete systems, engineers can create lightweight, durable, and resilient slope-support structures that withstand extreme climates and demanding conditions.

References:

- https://www.maccaferri.com/id/solutions/reinforced-soil-walls-and-slope-reinforcement/

- https://static.rocscience.cloud/assets/resources/learning/hoek/Practical-Rock-Engineering-E.Hoek-2023.pdf

- https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/sr/sr176/176-007.pdf